CHẤT LƯỢNG CAO NHẤT - GIÁ THẤP NHẤT - ĐẢM BẢO SỰ HÀI LÒNG

Cancers

2 Sản phẩm liên quan Cancers

How Cancer Starts

Cell changes and cancer

All cancers begin in cells. Our bodies are made up of more than a hundred million million (100,000,000,000,000) cells. Cancer starts with changes in one cell or a small group of cells.

Usually we have just the right number of each type of cell. This is because cells produce signals to control how much and how often the cells divide. If any of these signals are faulty or missing, cells may start to grow and multiply too much and form a lump called a tumour. Where the cancer starts is called the primary tumour.

Some types of cancer, called leukaemia, start from blood cells. They don't form solid tumours. Instead, the cancer cells build up in the blood and sometimes the bone marrow.

For a cancer to start, certain changes take place within the genes of a cell or a group of cells.

Genes and cell division

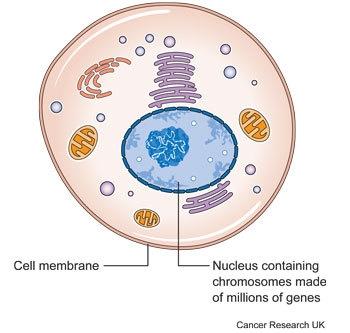

Different types of cells in the body do different jobs, but they are basically similar. They all have a control centre called a nucleus. Inside the nucleus are chromosomes made up of long strings of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA contains thousands of genes, which are coded messages that tell the cell how to behave.

Each gene is an instruction that tells the cell to make something. This could be a protein, or a different type of molecule called RNA. Together, proteins and RNA control the cell. They decide what sort of cell it will be, what it does, when it will divide, and when it will die.

Gene changes within cells (mutations)

Normally genes make sure that cells grow and reproduce in an orderly and controlled way. They make sure that more cells are produced as they are needed to keep the body healthy.

Sometimes a change happens in the genes when a cell divides. The change is called a mutation. It means that a gene has been damaged or lost or copied twice. Mutations can happen by chance when a cell is dividing. Some mutations mean that the cell no longer understands its instructions and starts to grow out of control. There have to be about half a dozen different mutations before a normal cell turns into a cancer cell.

Mutations in particular genes may mean that too many proteins are produced that trigger a cell to divide. Or proteins that normally tell a cell to stop dividing may not be produced. Abnormal proteins may be produced that work differently to normal.

It can take many years for a damaged cell to divide and grow and form a tumour big enough to cause symptoms or show up on a scan.

How mutations happen

Mutations can happen by chance when a cell is dividing. They can also be caused by the processes of life inside the cell. Or they can be caused by things coming from outside the body, such as the chemicals in tobacco smoke. And some people can inherit faults in particular genes that make them more likely to develop a cancer.

Some genes get damaged every day and cells are very good at repairing them. But over time, the damage may build up. And once cells start growing too fast, they are more likely to pick up further mutations and less likely to be able to repair the damaged genes.

How cancers grow

Benign and cancerous (malignant) tumours

Tumours (lumps) can be benign or cancerous (malignant). Benign means it is not cancer.

Benign tumours

- Usually grow quite slowly

- Don't spread to other parts of the body

- Usually have a covering made up of normal cells

Benign tumours are made up of cells that are quite similar to normal cells. They will only cause a problem if they

- Grow very large

- Become uncomfortable or unsightly

- Press on other body organs

- Take up space inside the skull (such as a brain tumour)

- Release hormones that affect how the body works

Malignant tumours are made up of cancer cells. They

- Usually grow faster than benign tumours

- Spread into and damage surrounding tissues

- May spread to other parts of the body in the bloodstream or though the lymph system to form secondary tumours. Spreading to other parts of the body is called metastasis

How cancers get bigger

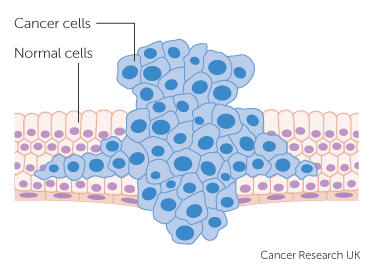

To start with, cancer cells are contained within the body tissue from which they have developed – for example, the lining of the bladder or the breast ducts. Doctors call this superficial cancer growth. It may also be called carcinoma in situ.

The cancer cells grow and divide to create more cells and will eventually form a tumour. A tumour may contain millions of cells. All body tissues have a layer keeping the cells of that tissue inside called the basement membrane. Once the cancer cells have broken through the basement membrane it is called an invasive cancer.

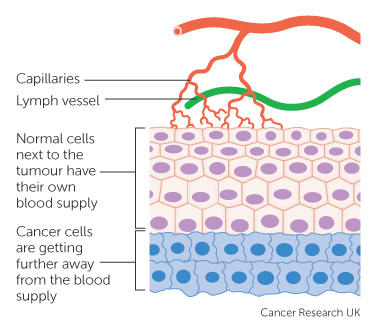

As the tumour gets bigger, the centre of it gets further and further away from the blood vessels in the area where it is growing. So the centre of the tumour gets less and less of the oxygen and the other nutrients all cells need to survive.

Like healthy cells, cancer cells cannot live without oxygen and nutrients. So they send out signals, called angiogenic factors, that encourage new blood vessels to grow into the tumour. This is called angiogenesis. Without a blood supply, a tumour can't grow much bigger than a pin head.

Once a cancer can stimulate blood vessel growth, it can grow bigger and grow more quickly. It will stimulate the growth of hundreds of new capillaries from the nearby blood vessels to bring it nutrients and oxygen.

Research into blood vessel growth (angiogenesis)

A lot of research is going on into angiogenesis. The research has found that the amount of angiogenic factors is very high at the outer edges of a cancer. Drugs that stop blood vessel growth (anti angiogenic drugs) can stop a cancer from growing into surrounding tissue or spreading. They can't usually get rid of a cancer completely, but may be able to shrink it or stop it growing in some cases.

Some anti angiogenic drugs can control certain types of cancer. More of these drugs are being developed and tested all the time.

How cancer spreads into surrounding tissues

As a tumour gets bigger, it takes up more room in the body. The cancer can then cause pressure on surrounding structures. It can also grow directly into body structures nearby. This is called local invasion. How a cancer actually grows into surrounding normal body tissues is not fully understood.

A cancer may just grow out in a random direction from the place where it started. However, tumours can spread into some tissues more easily than others. For example, large blood vessels that have very strong walls and dense tissues such as cartilage are hard for tumours to grow into. So locally, tumours may grow along the 'path of least resistance'. This means that they probably just take the easiest route.

Research has pointed to 3 different ways that tumours may grow into surrounding tissues and they are outlined here. A particular tumour will probably use all 3 of these ways of spreading. Which way is used most will depend partly on the type of tumour, and partly on where in the body it is growing.

Pressure from the growing tumour

As the tumour grows and takes up more space, it begins to press on the normal body tissue nearby. The tumour growth will force itself through the normal tissue, as in the diagram below.

The finger like appearance of the growth happens because it is easier for the growing cancer to force its way through some paths than others. For example, cancers may grow between sheets of muscle tissue rather than straight through one particular muscle.

As the cancer grows, it will squeeze and block small blood vessels in the area. Due to low blood and oxygen levels, some of the normal tissue will begin to die off. This makes it easier for the cancer to continue to push its way through.

Using enzymes

Some normal cells produce chemicals called enzymes that break down cells and tissues. The cells use the enzymes to attack invading bacteria and viruses. They also use them to break down and clear up damaged areas in the body. The damaged cells have to be cleared away so that the body can replace them with new ones. This is all part of the natural healing process.

Many cancers contain larger amounts of these enzymes than normal tissues. Some cancers also contain a lot of normal white blood cells, which produce the enzymes. They are part of the body's immune response to the cancer. We're not yet sure where the enzymes come from, but they are likely to make it easier for the cancer to make a pathway for itself through the healthy tissue.

As the cancer pushes through and breaks down normal tissues, it may cause bleeding due to damage to nearby blood vessels.

Cancer cells moving through the tissue

One of the things that makes cancer cells different to normal cells is that they can move about more easily. So it seems likely that one of the ways that cancers spread through nearby tissues is by the cells directly moving.

Scientists have discovered a substance made by cancer cells which stimulates them to move. They don't know for sure yet, but it seems likely that this substance plays a big part in the local spread of cancers.

This research is interesting because, if a substance has been found that helps cancer cells move, then researchers can start to find ways to stop the substance working. They may also be able to find ways to stop the cancer cells making the substance in the first place. If cancers can be stopped from spreading, it may be easier to cure them.

Researchers are also trying to understand how cancer cells change shape as they move and spread to other parts of the body.

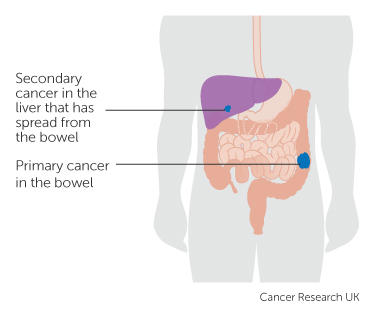

Primary and secondary cancer

The place where a cancer starts in the body is called the primary cancer or primary site. If cancer cells spread to another part of the body the new area of cancer is called a secondary cancer or a metastasis.

Some cancers may spread to more than one area of the body to form multiple secondaries or metastases (pronounced met-as-tah-seez).

How cancer can spread to other areas of the body

Cancer cells can be carried in the bloodstream or lymphatic system to other parts of the body. There they can start to grow into new tumours. The diagram shows a primary bowel cancer that has spread to the liver.

In order to spread, some cells from the primary cancer must break away, travel to another part of the body and start growing there. Cancer cells don't stick together as well as normal cells do. They may also produce substances that stimulate them to move.

The diagram shows a tumour appearing in cells lining a body structure such as the bowel wall. The tumour grows through the layer holding the cells in place (the basement membrane).

Some cells can then go into small lymph vessels or blood vessels called capillaries in the area.

Spread through the blood circulation

If the cancer cells go into small blood vessels they can then get into the bloodstream. They are called circulating tumour cells.

Researchers are currently looking at using blood tests to find circulating tumour cells to diagnose cancer and avoid the need for tests such as biopsies. They are also looking at whether they can test circulating cancer cells to predict which treatments will work best for each patient.

The circulating blood sweeps the cancer cells along until they get stuck somewhere. Usually they get stuck in a very small blood vessel called a capillary.

Then the cell must move through the wall of the capillary and into the tissue of the organ close by. The cell can multiply to form a new tumour if the conditions are right for it to grow and it has the nutrients that it needs.

This is quite a complicated journey and most cancer cells don't survive it. Probably, out of many thousands of cancer cells that reach the blood circulation only a few will survive to form a secondary cancer (metastasis).

Some cancer cells are probably killed off by the white blood cells in our immune system. Others cancer cells may die because they are battered around by the fast flowing blood.

Cancer cells in the circulation may try to stick to platelets to form clumps to give themselves some protection. Platelets are blood cells that help the blood to clot. This may also help the cancer cells to be filtered out in the next capillary network they come across so they can then move into the surrounding tissues.

Spread through the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system is a network of tubes and glands in the body that filters body fluid and fights infection. It also traps damaged or harmful cells such as cancer cells.

If cancer cells go into the small lymph vessels close to the primary tumour they can be carried into nearby lymph glands. The cancer cells may get stuck there. In the lymph glands they may be destroyed but some may survive and grow to form tumours in one or more lymph nodes. Doctors call this lymph node spread.

Micrometastases

Micrometastases are areas of cancer spread (metastases) that are too small to see. Some areas of cancer cells are too small to show up on any type of scan.

For a few types of cancer, blood tests can detect certain proteins released by the cancer cells. These may give a sign that there are metastases in the body that are too small to show up on a scan. But for most cancers, there is no blood test that can say whether a cancer has spread or not.

For most cancers the doctor can only say whether it is likely or not that a patient has micrometastases. This may be based on the following factors.

- Previous experience of many other patients treated in the same way. Doctors collect and publish this information to help each other

- Whether cancer cells are found in the blood vessels in the tumour removed during surgery (for example in testicular cancer). If cancer cells are found then cancer cells are more likely to have reached the bloodstream and spread to somewhere else in the body

- The grade of the cancer (how abnormal the cells are) – the higher the grade, the more quickly the cancer is growing and the more likely that cells have spread

- Whether lymph nodes removed during an operation contained cancer cells (for example in breast cancer or bowel cancer). If the lymph nodes contained cancer cells this shows that cancer cells have broken away from the original cancer. But there is no way of knowing whether the cells have spread to any other areas of the body

This information is important in treating cancer. If the doctor thinks it is likely that micrometastases are present, they may offer extra treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biological therapy or hormone therapy. The aim is to kill any areas of cancer cells before they grow big enough to be seen on a scan. So the extra treatments may increase the chance of curing the cancer.

Effects of cancer drugs on blood cells

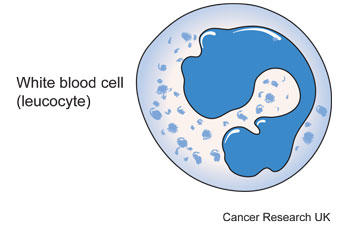

Some types of cancer drugs can lower the number of white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets in your blood for a time. Drugs that can cause this include some chemotherapy drugs and some biological therapy drugs.

Developing blood cells multiply all the time as they mature in the bone marrow and are then released into the blood. Some cancer drugs can slow the production of blood cells by the bone marrow so they are not released as quickly into the blood. Then the number of circulating blood cells goes down.

The level of white cell counts goes down first, because many white cells naturally die off within a few days. Normally these are replaced by newly developed white cells. But cancer drugs may kill some of the developing white cells. It usually takes a week or two before more cells can be made in the bone marrow and get back into the blood.

Mature red blood cells live for about three months, so there are fewer multiplying at any one time. So you often don't get low in red cells (anaemic) until further into your cancer drug treatment course. If your red blood cell level gets very low you may need to have a blood transfusion.

The platelet level may also drop. If it does, you may get nose bleeds, or notice a red rash on your skin like tiny bruises. You may then need to have a platelet transfusion. After high dose chemotherapy it can take longer for the platelet count to get back to normal than any other blood cell count.

Types of cancer

The main categories of cancer

Our bodies are made up of billions of cells. The cells are so small that they can only be seen under a microscope. These cells are grouped together to make up the tissues and organs of our bodies. These cells are basically the same, but they vary in some ways. This is because the body organs do very different things. For example, nerves and muscles do very different things. So nerve and muscle cells have different structures.

Cancers can be grouped according to the type of cell they start in. There are 5 main categories

- Carcinoma – cancer that begins in the skin or in tissues that line or cover internal organs. There are a number of subtypes, including adenocarcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and transitional cell carcinoma

- Sarcoma – cancer that begins in the connective or supportive tissues such as bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, or blood vessels

- Leukaemia – cancer that starts in blood forming tissue such as the bone marrow and causes large numbers of abnormal blood cells to be produced and go into the blood

- Lymphoma and myeloma – cancers that begin in the cells of the immune system

- Brain and spinal cord cancers – these are known as central nervous system cancers

Cancers can also be classified according to where they start in the body, such as breast cancer or lung cancer.

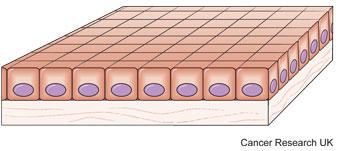

Carcinomas

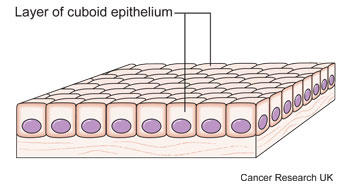

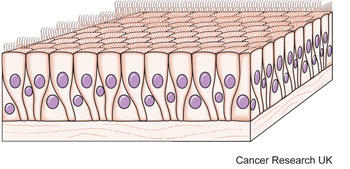

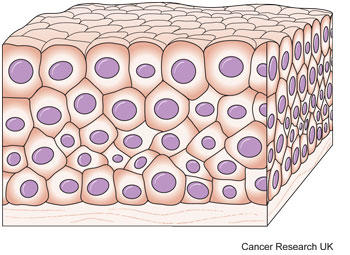

Carcinomas start in epithelial tissues. These cover the outside of the body as the skin. They also cover and line all the organs inside the body, such as the organs of the digestive system. And they line the body cavities, such as the inside of the chest cavity and the abdominal cavity.

Carcinomas are the most common type of cancer. They make up about 85 out of every 100 cancers in the UK (85%).

There are different types of epithelial cells and these can develop into different types of carcinoma. These include those below.

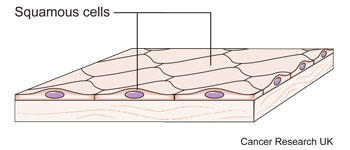

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma starts in squamous cells. These are the flat, surface covering cells found in areas such as the skin or the lining of the throat or food pipe (oesophagus).

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas start in glandular cells called adenomatous cells that produce fluids to keep tissues moist.

Transitional cell carcinoma

Transitional cells are cells that can stretch as an organ expands, and they make up tissues called transitional epithelium. An example is the lining of the bladder. Cancers that start in these cells are called transitional cell carcinoma.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cells are found in the deepest layer of skin cells. Cancers that start in these cells are called basal cell carcinomas. They are uncommon.

Sarcomas

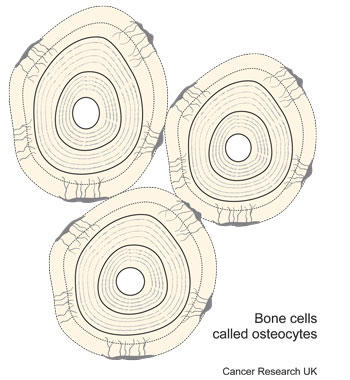

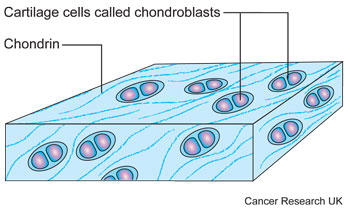

Sarcomas start in connective tissues, which are the supporting tissues of the body. Connective tissues include the bones, cartilage, tendons and fibrous tissue that support the body organs.

Sarcomas are much less common than carcinomas. They are usually grouped into two main types – bone sarcomas (osteosarcoma) and soft tissue sarcomas. Altogether, these make up less than 1 in every 100 cancers diagnosed (1%).

Bone sarcomas

Sarcomas of bone start from bone cells.

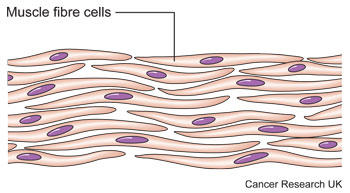

Soft tissue sarcomas

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare but the most common types start in cartilage or muscle.

Cartilage

Cancer of the cartilage is called chondrosarcoma.

Muscle

Cancer of muscle cells is called rhabdomyosarcoma.

You can find out more about soft tissue sarcomas.

Leukaemias – cancers of blood cells

Leukaemia is a condition in which the bone marrow makes too many white blood cells. The blood cells are not fully formed and so don't work properly to fight infection. The cells build up in the blood.

Leukaemias are uncommon and make up 3 out of 100 of all cancer cases (3%). But they are the most common type of cancer in children.

Lymphomas and myeloma – lymphatic system cancers

Lymphatic system cancers include lymphomas and myeloma.

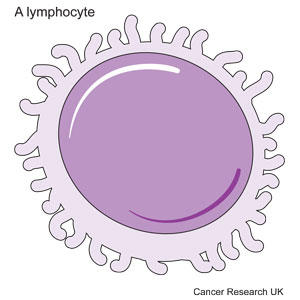

Lymphomas

Lymphomas start from cells in the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is a system of tubes and glands in the body that filters body fluid and fights infection. It is made up of the lymph glands, lymphatic vessels and the spleen.

Because the lymphatic system runs all through the body, lymphoma can start just about anywhere. Some of the white blood cells (lymphocytes) start to divide abnormally. And they don't naturally die off as they usually do. These cells start to divide before they are fully mature so they can't fight infection.

The abnormal lymphocytes start to collect in the lymph nodes or other places such as the bone marrow or spleen. They can then grow into tumours.

Lymphomas make up about 5 out of 100 of all cancer cases in the UK (5%).

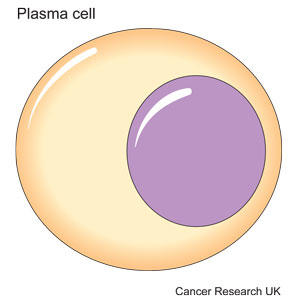

Myeloma

Myeloma is also known as multiple myeloma. It is a cancer that starts in plasma cells. Plasma cells are a type of white blood cell made in the bone marrow. They produce antibodies, also called immunoglobulins, to help fight infection.

In myeloma, the plasma cells become abnormal, multiply uncontrollably, and make only one type of antibody that does not work properly to fight infection.

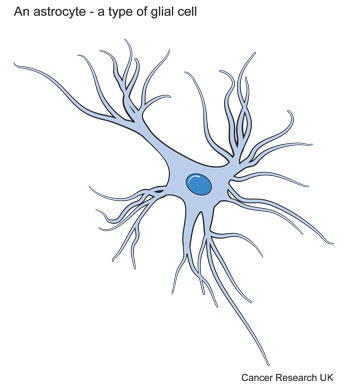

Brain and spinal cord cancers

Cancer can start in the cells of the brain or spinal cord. The brain controls the body by sending electrical messages along nerve fibres. The fibres run out of the brain and join together to make the spinal cord, which also takes messages from the body to the brain. Together, the brain and spinal cord form the central nervous system. The brain is made up of billions of nerve cells called neurones. It also contains special connective tissue cells called glial cells that support the nerve cells.

The most common type of brain tumour develops from glial cells and is called glioma. Some tumours that start in the brain or spinal cord are non cancerous (benign) and grow very slowly but others are cancerous and are more likely to grow and spread.

Stages of cancer

What cancer staging is

Staging is a way of describing the size of a cancer and how far it has grown. When doctors first diagnose a cancer, they carry out tests to check how big the cancer is and whether it has spread into surrounding tissues. They also check to see whether it has spread to another part of the body.

Cancer staging systems may sometimes include grading of the cancer, which describes how similar a cancer cell is to a normal cell.

Why staging is important

Staging is important because it helps your treatment team to know which treatments you need. If a cancer is just in one place, then a local treatment such as surgery or radiotherapy could be enough to get rid of it completely. A local treatment treats only one area of the body.

If a cancer has spread, then local treatment alone will not be enough. You will need a treatment that circulates throughout the whole body. These are called systemic treatments. Chemotherapy, hormone therapy and biological therapies are systemic treatments because they circulate in the bloodstream.

Sometimes doctors aren't sure if a cancer has spread to another part of the body or not. They look at the lymph nodes near to the cancer. If there are cancer cells in these nodes, it is a sign that the cancer has begun to spread. Cancer doctors call this having positive lymph nodes. The cells have broken away from the original cancer and got trapped in the lymph nodes. But it is not always possible to tell if they have gone anywhere else.

If cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes, doctors usually suggest adjuvant treatment. This means treatment alongside the treatment for the main primary tumour (chemotherapy after surgery, for example). The aim is to kill any cancer cells that have broken away from the primary tumour.

Types of staging systems

There are two main types of staging systems for cancer. These are the TNM system and the number system.

The systems mean that

- Doctors have a common language to describe the size and spread of cancers

- Treatment results can be accurately compared between research studies

- Guidelines for treatment can be standardised between different treatment hospitals and clinics

Some blood cancers or lymph system cancers have their own staging systems.

TNM stands for Tumour, Node, Metastasis. This system describes the size of the initial cancer (the primary tumour), whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, and whether it has spread to a different part of the body (metastasised). The system uses numbers to describe the cancer.

- T refers to the size of the cancer and how far it has spread into nearby tissue – it can be 1, 2, 3 or 4, with 1 being small and 4 large

- N refers to whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes – it can be between 0 (no lymph nodes containing cancer cells) and 3 (lots of lymph nodes containing cancer cells)

- M refers to whether the cancer has spread to another part of the body – it can either be 0 (the cancer hasn't spread) or 1 (the cancer has spread)

So for example, a small cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes but not to anywhere else in the body may be T2 N1 M0. Or a more advanced cancer that has spread may be T4 N3 M1.

Sometimes the letters a, b or c are used to further divide the categories. For example, stage M1a lung cancer (the cancer has spread to the other lung) and stage M1b lung cancer (the cancer has spread to other parts of the body).

The letter p is sometimes used before the letters TNM – for example, pT4. This stands for pathological stage. It means that the stage is based on examining cancer cells in the lab after surgery to remove a cancer.

The letter c is sometimes used before the letters TNM – for example, cT2. This stands for clinical stage. It means the stage is based on what the doctor knows about the cancer before surgery. The stage is based on clinical information from examining you and looking at your test results.

Number staging systems

Number staging systems usually use the TNM system to divide cancers into stages. Most types of cancer have 4 stages, numbered from 1 to 4. Often doctors write the stage down in Roman numerals. So you may see stage 4 written down as stage IV.

Here is a brief summary of what the stages mean for most types of cancer.

Stage 1 usually means that a cancer is relatively small and contained within the organ it started in.

Stage 2 usually means the cancer has not started to spread into surrounding tissue but the tumour is larger than in stage 1. Sometimes stage 2 means that cancer cells have spread into lymph nodes close to the tumour. This depends on the particular type of cancer.

Stage 3 usually means the cancer is larger. It may have started to spread into surrounding tissues and there are cancer cells in the lymph nodes in the area.

Stage 4 means the cancer has spread from where it started to another body organ. This is also called secondary or metastatic cancer.

Sometimes doctors use the letters A, B or C to further divide the number categories – for example, stage 3B cervical cancer.

Carcinoma in situ

Carcinoma in situ is sometimes called stage 0 cancer or 'in situ neoplasm'. It means that there is a group of abnormal cells in an area of the body. The cells may develop into cancer at some time in the future. The changes in the cells are called dysplasia. The number of abnormal cells is too small to form a tumour.

Some doctors and researchers call these cell changes 'precancerous changes' or 'non invasive cancer'. But many areas of carcinoma in situ will never develop into cancer. So some doctors feel that these terms are inaccurate and they don't use them.

Because these areas of abnormal cells are still so small they are usually not found unless they are somewhere easy to spot, for example in the skin. A carcinoma in situ in an internal organ is usually too small to show up on a scan. But tests used in cancer screening programmes can pick up carcinomas in situ in the breast or the neck of the womb (cervix).

Cancer grading

What grading is

You may hear your doctor talk about the grade of your cancer. Tumour grade describes a tumour in terms of how abnormal the tumour cells are compared to normal cells. It also describes how abnormal the tissues look under a microscope.

The grade gives your doctor some idea of how the cancer might behave. A low grade cancer is likely to grow more slowly and be less likely to spread than a high grade one. Doctors can't be certain exactly how the cells will behave. But the grade is a useful indicator.

Tumour grade is sometimes taken into account as part of cancer staging systems. The stage of a cancer describes how big the cancer is and whether it has spread or not.

Common grading systems

Some types of cancer have their own grading systems but generally there are 3 grades. They are described as

Grade 1 – The cancer cells look very similar to normal cells and are growing slowly

Grade 2 – The cells look unlike normal cells and are growing more quickly than normal

Grade 3 – The cancer cells look very abnormal and are growing quickly

Some systems have more than 3 grades.

GX means that the grade can't be assessed. It is also called undetermined grade.

Differentiation

Another way of describing the cells is by how differentiated they are. Differentiation refers to how well developed the tumour cells are and how they are organised in the tumour tissue. If the cells and tissue structures are very similar to normal the tumour is called well differentiated. These tumours tend to grow and spread slowly.

In poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumours the cells look very abnormal and the cells are not arranged in the usual way. So the normal structures and tissue patterns are missing. These tumours may be more likely to spread into surrounding tissues or to other parts of the body.

Cancer grade and treatments

Cancer treatment teams take into account the tumour grade and other factors such as the stage of a cancer, the person's age and their general health. This helps them to predict the likely outcome of the person's cancer and decide on the best treatment.

Generally, a lower tumour grade indicates a better outlook. A higher grade cancer may grow and spread more quickly and may need faster or more intensive treatment.

For some types of cancer the grade is very important in planning treatment and predicting outlook. These include soft tissue sarcoma, primary brain tumours, and breast and prostate cancer.

It is important to talk to your doctor for specific information about tumour grade and how it relates to your treatment and the possible outcome.

- Giới thiệu chung

- Kết nối cùng BRIAN IR

- Chính sách

- Trợ giúp

Đối tác thanh toán nội địa

Note : Chúng tôi mang đến cho các bạn những thông tin mới nhất trên thế giới về sức khỏe và cách chăm sóc sức khỏe. Những bài viết trên duocthiennhien.com mang tính chất cung cấp thông tin, không mang tính chất chẩn đoán, hoặc điều trị.

Sức khỏe là tài sản quý của mỗi chúng ta. Khi bạn cảm thấy trong người khó chịu hoặc mệt mỏi, hãy lắng nghe cơ thể của bạn và tìm cách điều chỉnh chế độ ăn uống và tập luyện của bản thân. Nếu bạn cảm thấy chưa yên tâm về sức khỏe của mình, hãy tìm đến lời khuyên của các bác sỹ hay chuyên gia y tế có Tâm và có Tài, để nhận được những chỉ dẫn cho sức khỏe của bạn. Đừng bao giờ nản chí, và đừng bao giờ chủ quan về sức khỏe của mình. Tri thức và hiểu được ngôn ngữ bản thân mình cũng rất quan trọng, bạn nên dành thời gian để nghiên cứu thêm về sức khỏe và hiểu được nhu cầu của cơ thể mình.

Nếu bạn muốn hủy bỏ đăng ký nhận thông tin về sức khỏe từ duocthiennhien.com, xin vui lòng bấm vào đây để hủy đăng ký

Điện thoại : 0243.990.2983 -*- Hotline : 0936.27.9939

Email : hendt.brianir@gmail.com